End to end PowerShell module deployment with Azure DevOps

We write a number of custom PowerShell modules at work, mostly for interacting with REST APIs of various services we use. A lot of this usage is on Hybrid Runbook Workers in Azure Automation, which are on-premise Windows systems. For years I’ve been trying to find a better way to deploy this modules than our old process of an Azure Automation runbook that copies the files to our production systems whenever a commit to master is made. And I think I’ve finally built something I’m happy with

Motivations

First, let’s dive into the motivations for this effort, or why I decided to rip out something that basically worked and replace it with something brand new.

Monolithic psm1 files

Our old way would copy whatever was in Git to the filesystem on every push to master. I wanted to use the paradigm of separating the functions each into their own file, further split into Public and Private folders. These would then be “built” into a single PSM1 file for deployment, but I wanted the files to be split for development.

Testing

The previous method had no testing built-in to the process. We used pull requests and code review, but all testing was manual, and usually took the form of running sections of code in a terminal with F8. I wanted to support test environments to deploy code to as we developed it. I wanted to use Pester to write tests for our code, run those tests automatically, and even prevent deployment if the tests failed. And I wanted this all to be automatic

Automation

I of course wanted this process to run automatically, but I wanted automation to take care of parts of the process. I wanted automatic versioning, so that we didn’t have to remember to update the version number each time. As I said above, I wanted to run tests automatically, and deploy to test environments automatically.

Easy to use

I wanted this process to be easy to use, both as someone who consumes it to deploy a module, but also as someone that maintains the process. I didn’t want to store the entire build process within each individual GitHub repo because then changes would need to be propagated across multiple projects manually every time the process was updated. I wanted the automation to happen, well, automatically, but I wanted to include the ability to configure it if the user so chose.

CI/CD

This is really a “solution” more than a “problem”, but I wanted to use a CI/CD tool like Azure DevOps for this process. Some of the requirements above also led me to wanting to use Azure DevOps templates, specifically.

The Result

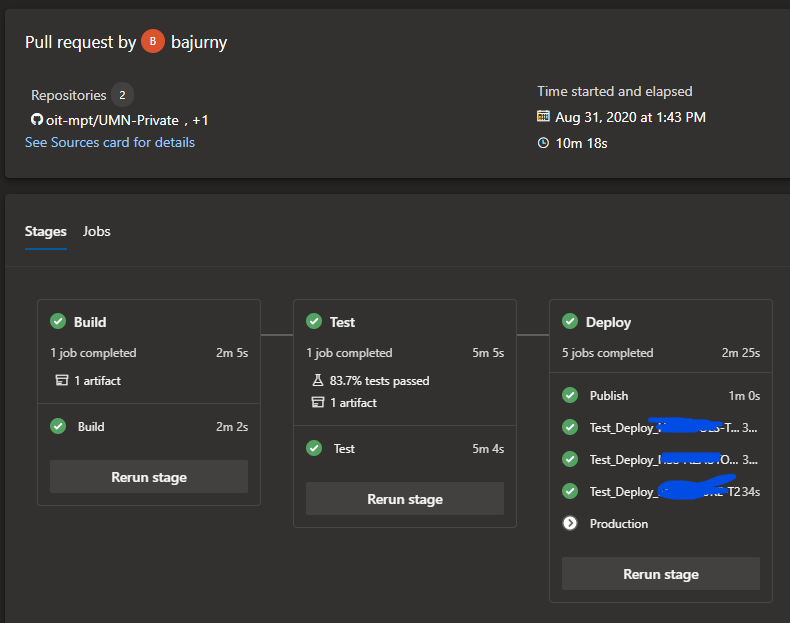

Above is a screenshot of the pipeline in action, for a module called UMN-Private. It’s a three stage pipeline - Build, Test, and then Deploy.

Build

This stage uses GitVersion to do automatic versioning. It also uses Install-RequiredModule to handle dependencies. Finally, it’s using ModuleBuilder to compile the module. This will result in a build artifact that will be a module with a single PSM1 file (built from the individual function files in source control) and versioned automatically by GitVersion (including pre-release verions for commits not to the default branch).

Test

The test stage will run any tests that are included in the Tests directory, as well as a few built-in tests. It will run PSScriptAnalyzer against the code, including a custom test to check if any strange characters are included in the code. It will also ensure that functions include help text, including parameter descriptions.

To assist with migrating old code, where you may not have the time or energy to fix every single failure of these built in tests, there is a variable in the template that can be used to define if the pipeline will fail on test failure or not. An example of that is shown in the image above, where only 83.7% of tests passed, but the task succeeded. Those failures were related to missing help text or PSSA violations in specific functions that I wasn’t working on at the time, and didn’t have time to fix completely.

Deploy

Deploy can mean a few things, but in its current state it means something pretty specific for our environment. Right now, this template only works for modules where the source code lives on our internal GitHub Enterprise server, and are not published to the PowerShell Gallery. The Deploy stage is actually a Publish job followed by a number of Deployment jobs.

The publish step will do two things. First, it will publish the module to our internal module repository using standard PowerShellGet commands. Second, for “release” versions, it will create a release in GitHub. This release is important, because it also creates a tag in git, and this tag is what GitVersion relies on to know what the current version is and what the future version will be.

Next up is the deployment jobs. While it’s not always a good idea to immediately push the latest version of new software upon release, it was one of our requirements. The reasoning for not doing this makes sense, you don’t want upstream changes to break existing processes. But in our case, we’re usually adding new functionality specifically so it can be used in existing deployments. Part of our review and testing is to do our best to make sure that we won’t introduce new issues with our new code.

Our deployment targets are all on-premise Windows virtual servers. The deployment is done using Environments, with a “Production” environment that gets release versions, and a “Test” environment that gets all builds. Each of these systems has an Azure DevOps agent installed on it, so that the deploy tasks can run directly against the machine. The deploy itself is fairly simple. It makes sure the correct repository is registered, installs the module, and attempts to install any external dependencies. Finally, it imports the module, to ensure that is properly installed and all dependencies are present.

The YAML

As I said earlier, this is all accomplished with templates. The templates are hosted on GitHub, and are publicly available. I love Azure DevOps templates, but I find they can be very confusing to read, so I’ve tried to make things easy to read. Module Projects will call the umn-module.yml file as their entry point. This template will take all the parameters passed in, and pass them into downstream templates, one per stage. Each of these stages may further call step templates. My attempt was to strike a balance between reducing the number of individual template files and making each file easy to understand in its own right.

azure-pipelines.yml

The gist below represents a sample pipeline file to consume this template

Repository layout

Unfortunately, all the current uses of this reside on our private GitHub instance, and can’t be shared externally. However I do have a work-in-progress project to make this process work with modules hosted on github.com. Most of the layout is dictated by requirements of ModuleBuilder. A directory for the source code is required, and should be defined in build.psd1. Inside that directory will be a stub psd1 file, a psm1 file that can be used during development, and Public and Private folders for individual function files. There is a Tests directory at the root that will contain any module specific tests you write. Requirements for building the module are listed in RequiredModules.psd1, to be used by Install-RequiredModule.

Conclusion

I would hope that what I’ve written is generalized enough that it could be useful for others, but what sent me down this path was finding other module templates that didn’t meet my needs. It is also currently built on a mountain of assumptions about the environment in which it will operate, few of them documented, and some I’m probably unaware of consciously. To that end, maybe it’s not useful as is for anybody else, but I hope that if nothing else it can provide path that others can follow

Comments